|

|

Margaret Fuller Q & A

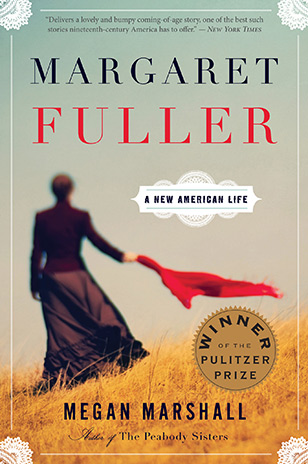

Praise | Q&A Margaret Fuller’s life story is as dramatic and inspiring as any I can think of–she was a brilliant thinker and writer, the comrade of Emerson and Thoreau, a pioneering journalist and daring feminist who lived out her ideals on a global stage. Then all of this ended for her in shipwreck and scandal at age forty. Writing a biography that captured the drama yet was true to the facts and conveyed the full complexity of Fuller’s ideas was the challenge I set myself. Relying on scholarship of the past three decades, which has made Fuller’s letters, journals, and all her published writing easily accessible, I drew connections between private correspondence and public testimony that helped me recreate key moments in her life in vivid new ways—her controversial relationship with Emerson, her secret love affair with Giovanni Ossoli, her anguish over leaving her infant son with a wet nurse in the Italian countryside while she covered the Roman revolution as the first woman war correspondent. All of these episodes stood out to me clearly, at last, as I worked directly with her words from so many sources. And there were important new finds as well: a letter Emerson wrote two weeks after Fuller’s death listing Thoreau’s findings at the site of the shipwreck, engravings she owned in Rome that survived the wreck. These helped me compose an intimate account of the final days. So my biography of Margaret Fuller is a “new” life in that sense—a close reading of material collected by others, and that I collected myself, a vast resource that hadn’t yet been thoroughly mined for the purposes of a sharply focused narrative biography. Then, too, Fuller herself created a “new American life” with the daring choices she made. Few women in her day would boldly admit to such powerful ambition as she did at age fifteen: “I am determined on distinction.” Margaret Fuller was a self-made woman who stood up to and in many ways outshone some of America’s most famous self-made men.

You could say these classes for adult women that Fuller led in the 1840s in Boston were a combination of a solid college-level humanities course and a radical feminist consciousness-raising group. There were no colleges for women then, and Fuller saw women’s need for higher education as well as for a kind of rigorous self-examination that she believed could liberate them from conventional feminine roles. “What were we born to do?” she asked. Here, too, I had new information. While researching The Peabody Sisters, I found a rare record of the first sessions kept by a woman who attended them–one of the reasons I felt I had to write about Fuller next.

In my view, Fuller’s impact as editor of this publication–the foremost literary journal in nineteenth-century America–has been underestimated. Yes, she edited and in one case cruelly dismissed Thoreau’s work, while praising his rough talent. And, yes, she prodded others of the circle–Emerson, Theodore Parker, Bronson Alcott, among them–to submit their writing. As a document of that extraordinary intellectual moment, The Dial is unsurpassed. But she also published a lot of work by women, poetry and essays on women’s rights, including her own brilliant “The Great Lawsuit,” which she expanded into the first book on “the woman question” published in the United States. She put the cause of women on the agenda in a male intellectual environment, and had no hesitation in doing so.

After she wrote “The Great Lawsuit,” Fuller took a rare summer vacation on the western frontier–Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan–and what she saw there, along with the freedom she experienced in travel, changed her life. She saw Indians forced off their ancestral lands; she saw great stands of virgin forest sacrificed to fuel steamboats. She became an environmentalist even before Thoreau, and an advocate of human rights. She also knew she’d had enough of New England. Two years later she took a job as front-page columnist for Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune, moved to New York City, and never looked back. From there, it was on to Europe, where she settled in Italy in 1848, the year of revolutions. She called Italy “my America,” because she thought the popular uprisings there were more authentically democratic than the conformity and materialism of the New World.

As for Margaret Fuller’s affair with Giovanni Ossoli, the much younger soldier in the revolutionary Roman Guard: working with clues she actually printed in her dispatches for the New-York Tribune, I was able to piece together one of their early trysts, from the time when she “passed the line” into physicality and discovered with Giovanni “the existence of a new, vast, and tumultuous class of human emotions.” Very likely we will never find out when they married, whether before or after their son was born, but we know they weren’t married then.

I’ve given a lot of thought to this question. Some biographers believe it’s important to take a theoretical approach–feminist or psychoanalytic, for example. While I’m sensitive to issues of gender and psychology, I consider it my job to present my subject in her own words, to represent the world as she experienced it, so that the reader lives life along with Margaret Fuller or the Peabody sisters. I’m an active amateur musician, an accompanist on the piano, and I feel I’m doing something similar in writing a biography. I want to support the soloist (or the subject). There may be give and take, my voice will be heard, but the subject plays the melody. Sometimes while I’m writing I even hear faint music that I try to catch and set down in words, a distant tune that keeps me company in my work.

|