|

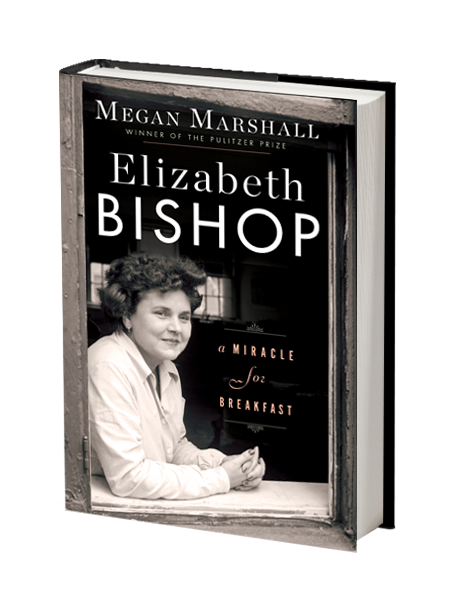

In PAPERBACK, December 5, 2017 |

|

PRAISE

“. . . a delight as well as a revelation . . .” “Marshall’s account is lively and engaging, charged with vindicating energy. . . . The book is ultimately about how words ordered on a page may supply some order for one’s life, may assuage and even redeem tragedy.” “Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast…helps fill in for devotees of Bishop’s work much of what couldn’t fit into one of her painstakingly perfected poems. And what we learn from Marshall’s book—informed by a mother lode of newly discovered letters—is that none of Bishop’s accomplishments could ever ease the pain of her loneliness...One advantage that Marshall has in telling Bishop’s story is her access to a trove of previously unavailable letters, which reveal the poet’s more intimate and personal side—the very facts that she guarded so zealously from others…Marshall utilizes this new material with elegance and craft worthy of her subject.” “A skillful and judicious performance . . . without any of the stiffness, the blockiness or monumentality that sometimes afflicts biography.” “This smooth and brisk presentation by a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of one of America’s most accomplished poets is enriched by recently discovered documents. Interweaving her own experience as a student of Bishop’s in the 1970s, Marshall skillfully discerns echoes between Bishop’s public and private writing.” “[Marshall] probes Bishop’s psychology, love life, and feelings about her contemporaries with surprising completeness. . . . Until now, our knowledge of Bishop’s personal life has largely been limited to her fractured relationship with the Brazilian Lota [de Macedo Soares]. . . . Marshall has unearthed more, some of it stunningly intimate.” “Using a wealth of new material, including the poet’s letters to her lovers and psychoanalyst, Marshall has crafted the most intimate and accurate biography yet available. Anyone interested in Bishop’s life and work will need to read this moving and often revelatory new account. . . . Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast is the rare sort of book that will expand the audience for contemporary poetry.” "A new biography of one of the most celebrated American poets of the 20th century. Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979) wasn't prolific—she published only 100 poems during her 40-year career—but she had a lasting impact on American letters. Pulitzer Prize winner Marshall was one of the aspiring poets Bishop taught in her final "verse-writing" class at Harvard in 1977. The experience was so profound that, upon discovering a trove of letters after Bishop's "close friend" Alice Methfessel died in 2009, Marshall set about to write this biography. The result is a sharp portrait of the tragedies and other influences that shaped Bishop's life and career. Bishop was only eight months old when her father died. After her mother was hospitalized for mental illness, Bishop was shuttled between her maternal grandparents in Nova Scotia, a place she loved, and her paternal grandparents in Worcester, Massachusetts. After these early scenes, Marshall documents Bishop's maturation as a writer; her struggles with alcoholism; her 17 years living in Brazil with her partner, architect Lota de Macedo Soares; her many affairs; and her relationships with such writers as Robert Lowell and Mary McCarthy. Best of all are Marshall's analyses of Bishop's poems, including "Song for the Rainy Season," "In the Waiting Room," and the book's subtitle. . . . The chapters on Bishop are written with often chilling exactness, as when Marshall describes the uncle who drew young Elizabeth's bath and gave her "an unusually thorough washing" or the polio-stricken admirer who killed himself after Bishop rejected him. His suicide note read, "Elizabeth. Go to hell." Bishop shared with Marianne Moore a "near obsession with accuracy of detail and precision of language." This fine biography demonstrates the magnitude of Bishop's achievements without ignoring her flaws."

Q & A

Yes–most definitely! The last major biography of Elizabeth Bishop was published in the early 1990s, almost twenty-five years ago, when both biographer and readers weren’t quite ready for a book that was open about the personal life of a poet who was herself so private, so insistently closeted, even though she lived into the era of Gay Liberation. But I’m not “outing” Elizabeth Bishop. My goal was to learn how her one hundred poems (that’s all she published, she was so meticulous) fit into her life, to uncover their sources in particular moments and memories, even as her consummate craftsmanship, her instinctive originality, made her poetry timeless, universal, “immortal,” according to her great friend Robert Lowell. Just as important as the changing times has been a cache of letters, Bishop’s most intimate correspondence, previously thought to be lost or destroyed, that was discovered after the death of her last lover, Alice Methfessel, in 2009. These letters made it possible to write with sympathy and precision about the end of Bishop’s long love affair–really a marriage–with Brazilian modernist designer Lota de Macedo Soares; to learn about the scary dysfunction in Bishop’s family life as a child and her teenage sexual awakening from a series of letters written to her psychoanalyst; to understand the profound attachment she felt for Alice Methfessel in a late-life second (or third or fourth!) sexual awakening that enabled her to write again after the calamitous breakup with Lota, who’d died of a drug overdose during an attempted reconciliation. Why the subtitle: “A Miracle for Breakfast”? I love this title Elizabeth Bishop chose for the first of two sestinas she wrote, helping to make this centuries-old verse form popular again. It’s not a poem that’s easy to understand, but it contains everything that’s wonderful about Bishop’s poetry–the delight in everyday rituals, like drinking coffee at breakfast; the sense that, with close observation, tiny things can be hugely meaningful; and a wry acceptance that for most of us, as the poem concludes, “the miracle” might be “working,” but “on the wrong balcony.” A passage in one of Elizabeth’s Bishop’s early journals reveals that she got the idea for the poem while living in Greenwich Village in the 1930s, shortly after graduating from Vassar. She was lonely, at loose ends, unsure of whether she’d make it as a poet, probably drinking too much. She’d woken up to find she had no food in her apartment, when she heard a call on the stairs–a representative of Wonder Bread bakeries was offering free slices of this brand new product. Suddenly she had something to eat, provided by a woman so down on her luck she’d taken a demeaning job passing out free samples for one of the few businesses that thrived in the Depression. Elizabeth titled this anecdote “A Little Miracle” in her journal, but it took three years and plenty of other experiences for the idea to become the poem, which actually has little to do with the original event. Following Bishop’s imaginative process was thrilling, but this poem is also the one that John Ashbery, one of the great American poets of the next generation, chose to read at her memorial service forty years later in 1979. He loved it too. And the sestina form grabbed me. I saw how the words at the end of each line, repeated in a prescribed pattern through six stanzas of six lines each, could become chapter titles for the six biographical chapters in my book. Suddenly I started seeing those end words–balcony, crumb, coffee, river, miracle, sun–everywhere in Bishop’s writing, not just in the poetry, but also in the prose (she wrote some remarkable short stories) and correspondence. You knew Elizabeth Bishop as your teacher in the 1970s. Did that make it more difficult to write an objective biography? Although I took a writing workshop at Harvard, where I was a scholarship student, with Elizabeth Bishop–“Advanced Verse-Writing” was her name for the class–I didn’t know her well at all. Her classes were quite structured and formal, and she was very shy, not comfortable holding forth or dispensing wisdom. Some of her students became her friends, but I wasn’t one of them. In fact there was a little problem between us that plays out in the brief autobiographical sections that alternate with the longer biographical chapters of the book. How well do we know the people in our lives? How well can a biographer know her subject, relying only on primary documents and remembered accounts? The alternating chapters of Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast–biography followed by memoir followed by more biography–take on these questions indirectly. The reader sees Elizabeth Bishop as I knew her in real time, at the end of her life, alongside Elizabeth Bishop as she experienced her own life, going through it from birth to death. One of the surprising results is that the reader gets closer to Elizabeth Bishop, experiencing her vicariously through my eyes. The essential mystery of what enables a person of genius to realize her talent is still there, but we see Elizabeth Bishop at first hand struggling to solve that problem. And it was a problem I struggled with too, how to make use of my own lesser capabilities and manage my fledgling ambitions as a student poet. We’ve all been there. I learned so much from Miss Bishop, as we called her, that wasn’t on her syllabus, and that I’ve come to appreciate more powerfully since college and while writing this book. Miss Bishop taught by living her life, and so it seems natural that I would one day write her biography. Although lives aren’t pre-determined, they take their own course and may not really have a coherent shape, there was something miraculous about the reverberations in our lives that I began to feel as I worked on the book, and a coincidence that seemed to bring us together at the end. Objectivity is always a relative matter in biography–the writer is either sympathetic to or in disagreement with her subject, or she wouldn’t put in the time. In this book, the stakes are clear, which made the work fascinating and draws back the veil for readers. Do you have a favorite Elizabeth Bishop poem? I loved writing about “One Art,” Elizabeth Bishop’s best known poem. There are seventeen drafts, so you can track the progression of her thoughts and feelings, witness her artistic decisions. And I learned more about the circumstances that inspired the poem: Elizabeth’s fear that she was losing Alice to a man she planned to marry. But “The Shampoo” has always been one of my favorites. It’s the most explicit love poem written for a woman that Elizabeth Bishop published (which means not very explicit). “The Shampoo” is about the way love infuses domestic ritual as she washes Lota’s long black hair, streaked with gray, on the patio outside the house they were building together on a mountainside in Brazil. (They had no indoor shower yet.) The poem ends with this beautiful, rhythmic, invitation:

|

|